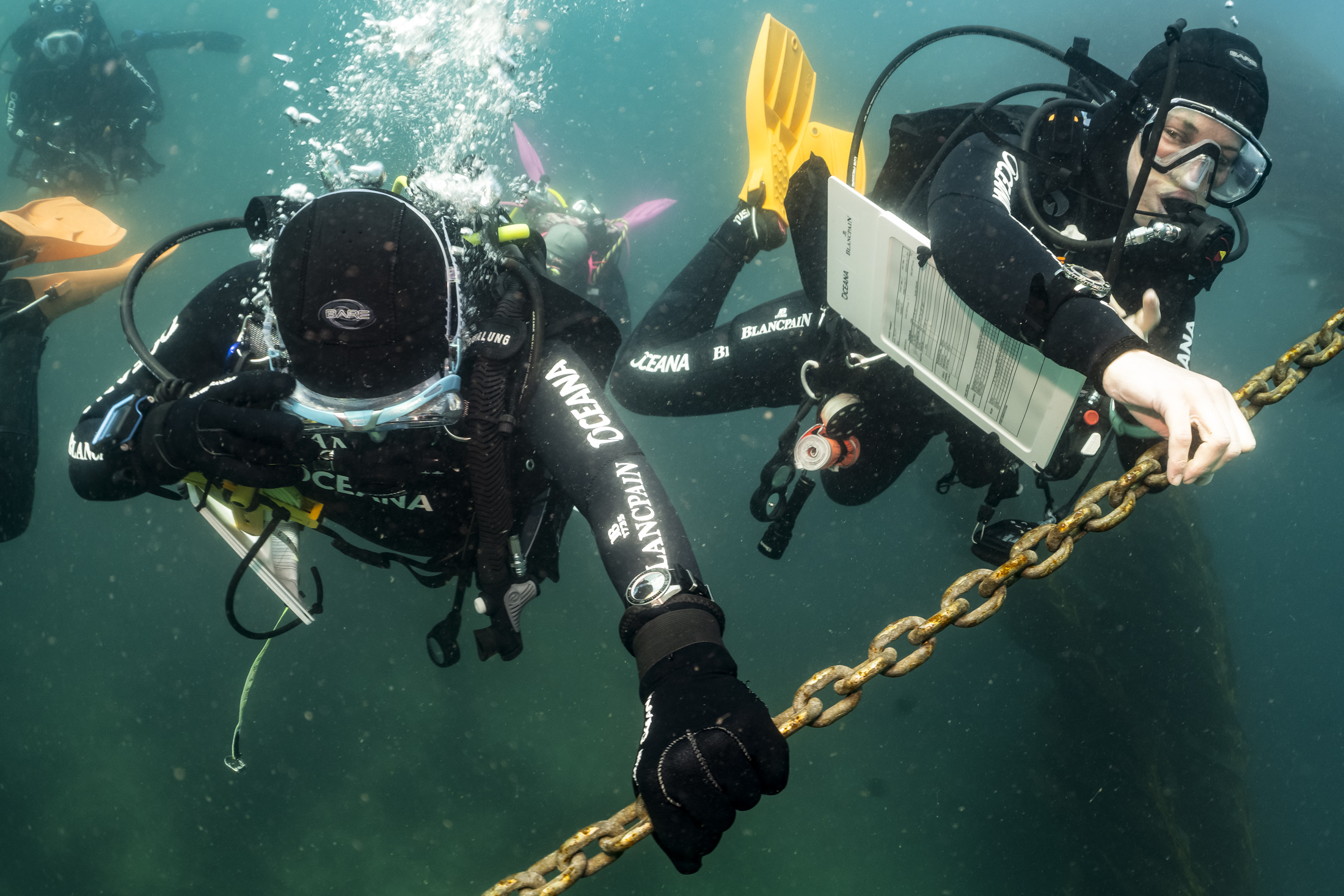

Science seems like one of those pursuits that consists of, to paraphrase a well-worn aphorism, "long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer excitement." This thought occurred to me while hovering at a depth of 50 feet in the kelp forest near Santa Barbara Island, off the coast of California. I was watching Dr. Adrian Munguia Vega perform a sort of underwater interpretative dance above me. He was neutrally buoyant and backlit by the distant sun, a mesh bag clipped to his belt and what looked like a hydration bladder in one hand, which he was swinging up and down in a slow arc. If I hadn't known what he was up to, I might have been concerned that he'd fallen victim to nitrogen narcosis. In reality, he was collecting water, one liter at a time – in the ocean.

I don't have the patience or the meticulous attention to detail (or the mental aptitude) to be a scientist, so it's a good thing I pursued a degree in English Literature. I like to tell stories, usually snapshots in time, about things I see and experience. Science is a long game, marked by slow, steady progress and a lot of setbacks. But it still needs storytelling – to convey results, to gain support, and to let people know why the work is important. And that's where I come in. This summer, I was embedded with a team of scientists from the marine conservation organization Oceana, living on a boat during two expeditions and diving around California's Channel Islands.

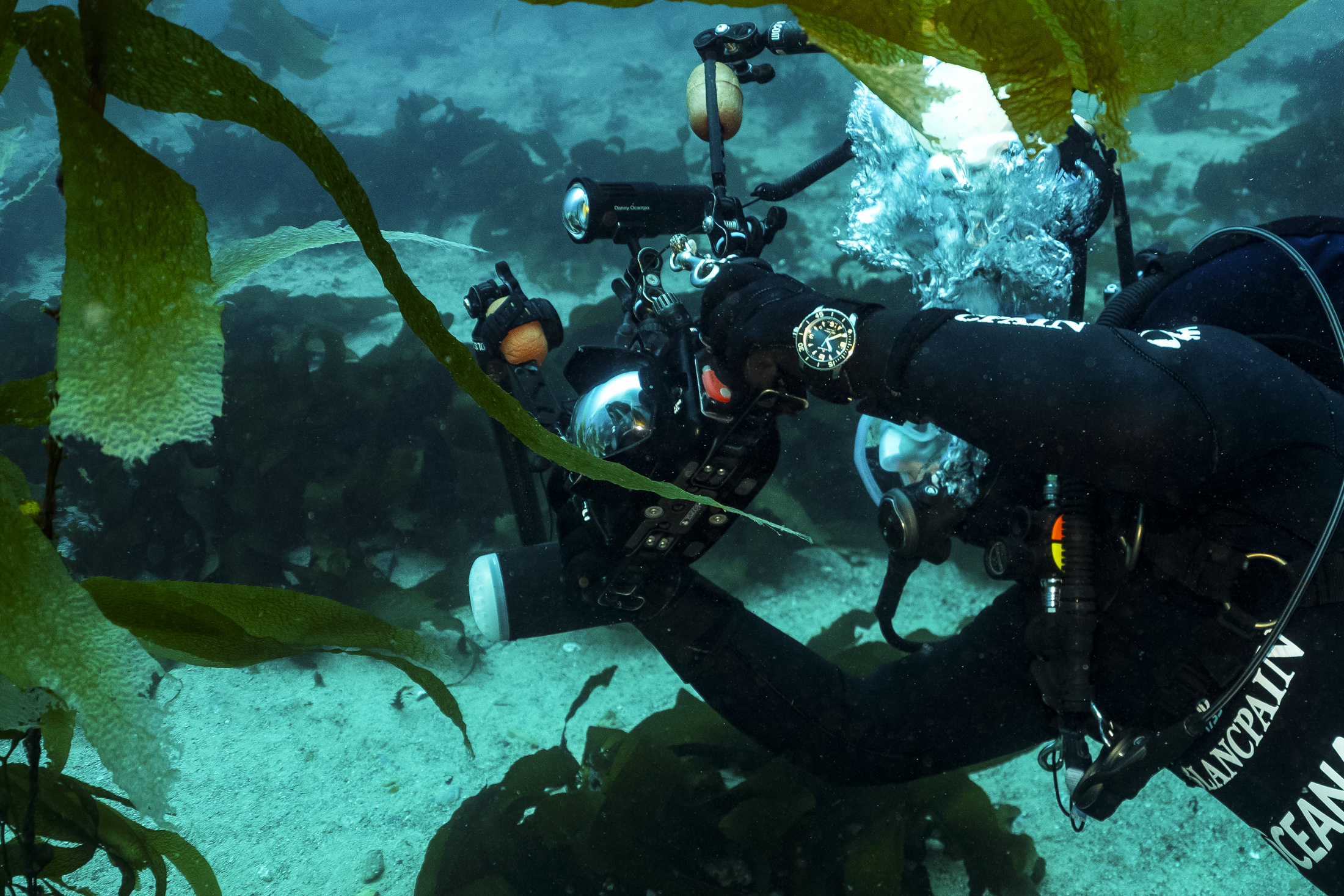

I was on the Peace Boat as a guest of the Swiss watch company Blancpain, the expeditions' primary underwriter, but this was no press junket. If I was onboard, I had to earn my keep. While the scientists were collecting data, whether by surveying the reefs with clipboards and measuring tapes or by collecting water samples for analysis, visual evidence was needed, too, and that meant taking photographs. Despite my years of subaquatic exploration, my knowledge of marine life is embarrassingly scant, so I relied on the other divers to point out anything unusual or significant to document in megapixels: a decorator crab, a kind of soft coral, or a horn shark. A secondary goal was to get photos of watches on wrists, and before you pass judgment on what might seem like a trivial, or dare I say shallow, focus, consider the unpleasant matter of the bill.

Oceana and Blancpain have a symbiotic relationship. Oceana needs funding to carry out its advocacy work and research, and expeditions like these in the Channel Islands are not cheap. There's the boat charter, the crew, all the food, travel expenses, and new equipment to pay for. Blancpain generously provided funding for not just one but three of these expeditions (the third one will take place in 2025). But, of course, Blancpain gets something out of the arrangement. The company, a renowned pioneer in dive watches, has a long history of supporting ocean exploration, marine science, and underwater photography. Their involvement with the ocean and diving has become inextricably woven into the company's branding and ethos, trickling down from its CEO, Mark A. Hayek – a passionate and expert diver himself – who I'm convinced would prefer to be on a dive boat anywhere than a boardroom. To be associated with Oceana is not only good optics for Blancpain but also something of a natural fit. Everybody wins. And we got to dive with some amazing watches.

We set off from Ventura's bustling marina, facing a choppy crossing through forecasted gale-force winds and rather big seas. With gear safely stowed, I retreated to my coffin-sized sleeping berth to ride out the two-hour voyage to the islands. The captain would play chess with the wind for the whole week, moving the boat among sheltered anchorages in the lee of the islands where we would dive, eat, and sleep in relative calm.

A diving expedition is a distilled experience, especially while living on a boat for five days. There's simply not a lot of room or privacy, and the day's activities become broken down into focused rituals of prepping gear, diving, downloading photos, eating, some sleep, then doing it again. We dove three times a day, and in cold water, sometimes kicking into current, with heavy gear on – it has a way of tiring one out. I slept well, a cocktail of residual nitrogen from breathing compressed air and meclizine from my motion sickness tablets sedating me and the swells rocking me into sweet oblivion.

The Channel Islands are sometimes referred to as the "Galapagos of North America" due to the rich diversity of their ecosystem. The waters around this rather haphazard necklace of eight islands are lush with the signature kelp, a plant that grows incredibly fast and incredibly tall. Diving in kelp is otherworldly and a little creepy if you're used to clear Caribbean reef diving. It is a veritable jungle with a canopy that can reach 60 or 70 feet up to the surface. Swimming among its swaying leaves and thick stalks is like bushwhacking through a forest, with the associated entanglement risks, and you're never quite sure what's around the bend. These islands are known to be great white shark nurseries and home to car-sized giant black sea bass, as well as harbor seals, sea lions, rays, and countless other species.

Though we didn't encounter any apex predators on our dives – which was both relieving and troubling – we had no shortage of surprises, from overly affectionate seals to iridescent Garibaldi fish to bottom dwellers like an encrusted decorator crab and the exotic angel shark. As part of an ecosystem survey, critters, and topography were noted by the divers with the waterproof pencils and those of us with cameras, but it's what's unseen that can still be discovered, and that's where Dr. Adrian came in. He is an expert in the analysis of "environmental DNA," or eDNA.

Think of it like a crime scene investigation underwater. That water he collects in his bag, or the water he brings up from 100 meters deep in a specialized tethered drop bottle, is then processed back on the boat using vacuum pressure and filters that capture the DNA present in the medium. The water is then discarded, and the filters, labeled for each location and time, are taken back to a lab for analysis, revealing every living creature that has passed through the water, including us, I suppose.

I've been fortunate to tag along on a few Blancpain-sponsored expeditions over the years. The first was a week-long journey to the remote Revillagigedo archipelago, then more recently to French Polynesia with a team of scientists researching great hammerhead sharks, and this year, twice to the Channel Islands – always the Pacific Ocean. This greatest of oceans does not live up to its name. The diving is often challenging – cold, with strong currents and murky visibility – but it rewards the committed diver with incredibly prodigious marine life. It requires fitness, attention, and care.

Blancpain seems like a fitting watch brand to wear for this kind of diving. I like to say that when you pay more for something, you should expect more from it, and while Blancpain is clearly in the upper echelon of luxury products, it somehow manages to retain credibility as a diving tool, whether because of its legacy, its branding, its thalassophilic CEO, or the high level of quality of its watches. Blancpain diving watches somehow manage to straddle haute horlogerie and sober functionality better than most other high-end timepieces, and I've seen my share of thoroughly scarred-up Fifty Fathoms that have been used as intended.

Case in point: on the Channel Islands expedition, we certainly didn't baby the watches. The divers took turns wearing a trio of Fifty Fathoms watches, and it was my duty as the onboard watch nerd to secure them to wrists with extra long nylon straps before we jumped into the briny deep. Blancpain provided a loaned Fifty Fathoms Automatique in steel, and I packed along my own titanium reference as well as my Hodinkee Limited Edition Bathyscaphe.

It was with a twinge of jealousy that I forfeited my own watches for the sake of photo opportunities, but being behind the camera meant my own wrist was wasted real estate. We joked that a photography goal for the week was not only watches on wrists underwater but a watch on a wrist, with some sort of charismatic marine animal in the background. Easier said than done. Photographing a small, shiny object underwater is hard enough, but to get a wild animal to cooperate adds an exponential layer of difficulty. But finally, on one of our last dives, I got the chance, and it happened to be with a watch on my own wrist.

The horn shark is a rather small, elusive fish that remains well camouflaged on the seafloor, often among the kelp. Its diet consists of mollusks and crustaceans that it roots out of the sand and then crushes with powerful jaws and grinding teeth. Its name comes from the tooth-like horn on the tip of its dorsal fin. It is a shy animal, rarely seen by divers, so when Anja, one of the scientific divers, waved for my attention and put her hand vertically on her head in the sign for "shark," my blood went cold, and I swiveled, scanning the water column with the Jaws theme playing in my head.

She pointed to the sand a few feet away in front of me, and I saw it – a horn shark, prone on the bottom, unmoving. I slowly finned over and hovered above it, firing off several frames in the name of science before extending my own left arm with my Bathyscaphe (a 50th birthday gift from Hodinkee, no less) strapped over my drysuit sleeve. I pulled the cumbersome camera housing as far back as I could to focus, hoping to get the watch and shark in the shot, and fired blindly. The shark had had enough and turned to swim away, disappearing among the kelp.

Back on the boat, I removed the camera from the housing, plugged the memory card into my laptop, and downloaded hundreds of images. Scrolling through them, I came to the series of photos with the shark. There, in perfect focus and well-lit by my powerful dive lights, was the horn shark. And there, in the next image, was my watch, slightly out of focus but legible, with that telltale shark shape behind it. I let out a whoop. My patience had paid off. And while it hadn't exactly been boring before, I could now relate to that "moment of sheer excitement."

I got the shot.

Top Discussions

Breaking News Patek Philippe's Ref. 5711 Nautilus Is Back As A Unique Piece For Charity

Found Three Of The Best Tourbillon Wristwatches Ever Made, For Sale This Week

Photo Report A Visit To Nomos Glashütte